Viral Nature

A composite material, fertile and able to host life made to grow into living botanical sculptures. #Nature’s Economies

Our bodies are microbial chimeras, symbiotic beings that co-evolve, co-become, and co-heal with. #Re-designing Infrastructures

Care is a word whose tendrils reach far and wide, in simultaneous directions, dancing and wrapping themselves into worlds of political and emotional gravity. It’s a meddlesome word, one which entangles beings in the most pregnant of ways, tying us in kin and kind, in tenderness and ardor, in simple and complex alliances of responsibilities and response-abilities. As a fundamental social practice, caring is everything we do to shape well-being, rendering it intrinsically difficult to decide who ought to care and how. It involves a certain maintaining of the world, of meeting needs – ours and that of others. How then, given its central role within our lives, can the institution of healthcare more democratically? Amidst mounting inequalities appearing within our systems of care, it is clear that caring institutions, and relationships need to be re-imagined to shape narratives in which care is not only a concept but a foundational tool for our becoming together.

In the contemporary western world, healthcare operates on the basis of highly entrenched paradigms. On one hand, we are told that our health is our own personal responsibility, a trademark narrative of modern neoliberal policies1. On the other, we are institutionally positioned as passive receivers of care, a product of the paternalistic doctor-patient relationship developed from a Greco- Roman history of medicine2. We care between a rock and a hard place because those are the historical structures we have been given. As an alternative to this practice of caring for, feminist care ethicists have suggested caring with3, an act of deep collaboration and co-operation as a means through which we can move beyond these paradigms towards a more collectivized and embodied form of healthcare.

Caring with requires the co-production of health practices, a notion which demands opening up the very production of what is considered ‘valid’ medical knowledge used in deciding what is and is not valid forms of healthcaring. In the West, this is determined through the scientific method, or ‘evidence-based research’. As this is used to legitimize practices of healthcare, it has also had the effect of delegitimizing the embodied knowledges built from people’s socio-cultural experiences of health4, what we might call our somatic phronesis. Ancient Greeks used the word phronesis to describe the wisdom and intelligence relevant to practical action 5. In the context of medicine, the physician bore the whole responsibility of caring for the patient because the ‘sick’ were considered to be devoid of phronesis. Despite a few stopgap measures along the way, most of which deal with the notion of patient consent 6, the perception that as patients we have little to no knowledges of our bodies relevant to care continues to be part of the underlying rhetoric within the medical world. This mistrust of patient’s abilities within Westernized forms of medical care contributed to the erosion and suppression of valuable knowledges and rituals related to health that were based on other cultural experiences, what philosopher Ivan Illich refers to as cultural iatrogenesis 7.

Here, the point is not to question the overall validity of the scientific method, but rather to recognize the way this practice of knowledge production has been used over time helped create a clear hierarchy of care systems — one in which medicine in the West, an essentially ethnographic practice, is considered the one and only ideal. Through historical processes of imperial colonialization and modern market forces of globalization, this singular practice of healthcare has spread across the world, actively suppressing other histories and embodied knowledges of care 8. But knowledge can come from embodied experience, and alternative praxes of care and healing often cannot be defined in the context of this method. If caring with implies the democratic allocation of care responsibilities between a care giver and care receiver, body-on governance – the agency of somatic phronesis – plays an integral role in establishing new practices of care.

When we breathe, when we touch, when we stick our wet tongues out in laughter towards invisible bodies of matter, letting shapeless substance rub along the fleshy linings of our being, we enter into unions with microbial companions. Through these entanglements, health becomes an incalculable set of tiny, perpetual rituals with invisible biological beings.

As an open and malleable synergetic system of micro-organisms that live in and on us, the human microbiome9 is easily influenced by the people we live in close proximity with. Even something as simple as walking barefoot in a shared home alters a person’s microbiome, positioning health as a relationship modulated through the flux of microbial matter. In a way, we are microbial chimeras10, symbiotic beings that co-evolve, co-become, and co-heal with. Western medical and pharmacological practices have already begun to develop treatments that enable the transplantation of microbiomes to address dysbiosis, a form of microbial imbalance linked to conditions such as Alzheimer’s11, depression12, autism13, and cancer14. As microbiome therapeutics represent ‘the new frontier’ in Westernized medicine and pharmacology15, careful thought needs to be put into how such novel therapies16 are designed. If symbiosis17 – the close, physical, long-term biological interaction between organisms and the main force behind species evolution – is the model from which caring with happens at the microscopic level, new models of healthcaring need to be designed with processes of collaboration between communities of organisms in mind18.

Our bodies contain the means for one person’s health to become another’s. Currently, this idea contrasts with Western medicine’s highly individualized, singular, and atomized19 understanding of the body. Nevertheless, if we are to care with treatments, therapies and medical processes aimed at restoring dysbiosis, these treatments will need to be thought of as mutualistic processes, as rituals of co-healing engaging not only a body but a congregation of bodies in continuous flux. Furthermore, if these rituals are to shift persisting paradigms and re-form Western healthcare practices, they must communalize this microbial flux by supporting body-on governance around microbiome health, which can only arise when valuing complex forms of somatic phronesis.

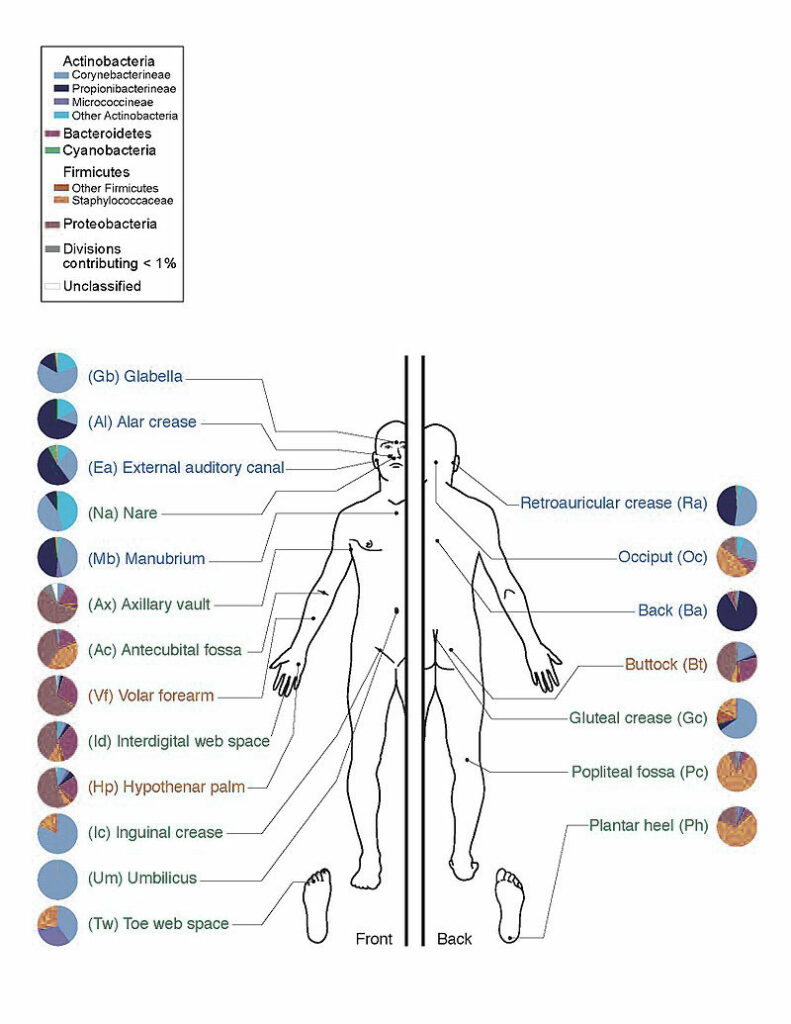

First depiction of the skin’s main bacterial species found at different sites.

Across the world, saunas, sentos, hammams and jjimjilbangs 20 were designed for people to engage in bodily rituals of grooming in an open and collective manner. These bathhouses simultaneously served (and in many cases continue to serve) recreational, social, ceremonial, hygienic, and medicinal roles 21. With this in mind, bathhouses act as prime examples of how communalized and embodied healthcare can be embedded within the design of a sociocultural group experience via performative, material and spatial conditions. This is very different from the common Western medical experience, which often is limited to private settings (such as the doctor’s office). Take the Turkish hammam, where multiple bodies scrub their skin on a common, soapy warmed slab of marble, or the Russian banya, in which the sweat of people whipping themselves with birch branches intermingles in a closed, heated room of cedar planks. These spaces provide people with a place for caring in the flesh with others, their design, and historical cultural and physical structures positioning grooming – a vernacular practice of medical care – as an integral part of the cultural fabric 22.

Sauna in Bautzen, Germany. https://eo.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dosiero:Fotothek_df_n-22_0000540_Sauna.jpg

Collectivized grooming also exists within the larger practice of public health and hygiene, a means through which communities prevent the spread of infectious disease and often takes the form of some sort of communal cleansing whose performance directly or indirectly benefits public health. As a commonplace, everyday ritual intricately tied to the body, grooming serves as an interesting point from which to approach microbial co-healing, most notably when spatialized within the typology of a bathhouse. Such is the starting point of The Microbial Bathhouse, a research platform into the practice of co-healing and a space for experimentation around new forms of caring with that include microbes in ritualized healthcaring.

One of the first experimentations into spatialized microbial grooming is a multisensorial installation facilitated around the Lung Microbiota Exchange Tool, a medical device developed in collaboration with a medical microbiologist and a scientific glassblower. With an experience akin to that of a traditional sauna, the installation, provides co-healers with steam-based microbial grooming for the lungs in a room heated between 35 and 37 degrees Celsius, a temperature favored by the body’s microorganisms. Throughout this experience, microbial flux travels in an out of the body of microbial chimeras, being collected and reshared in a ritualistic manner through artefacts of care which depart from the commonly sterile language of Western medicine. Microbes from the respiratory tract are collected during a ritual of Giving, where co-healers blow into a glass vessel containing a liquid which can safely hold microbes while outside of the microbial chimera’s body. This begins the process of a safe exchange of microbes from the respiratory tract to support the diversification of the microbial population necessary to prevent or help treat chronic respiratory diseases. This process thus contextualizes the practice of microbial grooming in the public setting of the bathhouse, positioning people’s health – via their microbial body – as a shared resource.

After multiple co-healers have engaged in the Giving ritual, the microbial broth is transferred to another glass vessel for twenty-four hours where microorganisms multiply significantly 23. Finally, the microbial liquid is transferred into a ceramic vessel and then transformed into a fine particulate that can be inhaled. During the Receiving ritual, co-healers scoop up the microbial steam with a glass spoon designed to hold mist. They inhale tiny droplets of microbial mist, helping the rich and diverse collection of microbes to travel into the respiratory tract.

Supporting this ritualized processes of microbial co-healing are various borosilicate glass tools whose asymmetrical shapes depart from traditional laboratory and medical equipment 24. The design of the objects forms a different typology of medical instruments reflecting the notion of embodiment. For example, each was designed with the intention of integrating the bodies that produced them, such as using the variations in the scientific glassblower’s breathing patterns to shape asymmetrical medical apparatus.

The somatic medical experience that takes place in The Microbial Bathhouse positions people as symbiotic co-healers that can act as both caregivers and care receivers. Within current pharmacological industries, many if not all microbiome therapeutics are conceived as drugs in which the process of donating and receiving does not happen simultaneously. Instead, a donor provides a cultured sample which is sent to a microbiology lab for screening, and then either strains from the culture are synthesized into a drug or the culture is packaged into a format that can be administered to the receiver. This is a highly medicalised process where each party is isolated from one another throughout this process of exchange. With the Lung Microbiota Exchange Tool, co-healers destabilize the highly procedural and depersonalized processes of microbiome transplants, experiencing them as microbial grooming rituals instead of clinical actions. While traditional medical professionals such as doctors and microbiologists were consulted in order to shape something that was cognizant of the necessary safety and wellbeing of participants 25, the shape of the tools and the space itself departs from the clinical rigidity which many of us have come to understand as visual markers of our healthcare system.

To live in a time of virulent fear changes our relationship to microbes in many ways. If the last couple of years saw the beginning of a post-Pasteurian26 trend in popular understanding of microbes and health, progress of developing a better relationship with our microbial ecosystems of health has been short-circuited by the global pandemic of the Coronavirus. Even before it was dominated by the use of antimicrobial cleaners and hand sanitizers, Western public health messaging reflected an antibiotic worldview, a prevailing paradigm that’s had surmounting negative ramifications across the globe27. That the world is in a state of dysbiosis calls for the opening up of health practices that foster more-than-antibiotic28 relationships with our bodies and our health, practices that see beyond the limitations of the virus. If anything, our new reality highlights how deeply we are microbially woven, through processes and relationships that must be maintained and nurtured both in microscopic and macroscopic ways. To care with each other as microbial chimeras is to demand a high level of mutual trust and acceptance of inter-dependency. Let us learn to care with our somatic phronesis and to shape medical experiences that are collective, open, and agency-inducing. Amidst rising inequalities in matters of care, shaping new narratives around co-healing with microbiotic kinships is imperative. If anything, this is an urgency to outlast any virus.

Bibliography

Serina Tarkhanian is a designer and researcher whose work explores contemporary issues around care and the social conditions of health and well-being. She has recently completed a master’s degree in Social Design at Design Academy Eindhoven with her project Co-Healing: An Institutional Reform for Caring With (Cum Laude, Gijs Bakker Award nomination, Best Thesis Award) after working in design for a decade as an interactive experience designer. Her work can be experienced across many continents, mainly in Canada (Montreal Science Center, Canadian Olympic Experience, Museum of Ingenuity J.-A. Bombardier), the UAE (Healthy Champions, Dubai Children’s Museum), and Europe (Fuorisalone, IT).